Within the IoT landscape, there is a plethora of different products sold to individual consumers – some good, some not so. Therefore, this label has been introduced to evaluate IoT products and offer support to consumers to make secure choices so their own environment is not placed in jeopardy.

It has been a little over a year since the label’s introduction, and it now has nine products assigned to it. “These are the first nine products that have any kind of National Cyber Security label,” said Vasenen. “So Finland, and Traficom, were the first organisation to launch an IoT security label for consumer IoT devices.

“During the first year, most of the technical work was done by the NCSC. However, now as we are trying to scale everything up, we hope that commercial inspecting bodies will provide the services for manufacturers. From the consumer’s point of view, the cyber security label is a lock symbol. There’s a QR code, which points the consumer to our website that contains more details on the products.”

This means that consumers can scan the QR code of any product carrying the label. The website also contains the statement of compliance where the manufacturer provides more details on how security is handled by the product, and there are a variety of applications represented by the nine products already certified. There are three smartwatches, a smart weather station, a mobile application with Bluetooth connectivity features, a smart home thermostat system, an IoT gateway, and a home lighting system.

Label requirements

Vasenen highlighted that there are a number of different kinds of security schemes, while explaining the factors that set the Finnish label apart. “Ours is slightly different. The aim is to provide a way to make sure that consumers are protected against realistic threats from the internet. That was the main goal, not just technical lists of things that need to be handled accordingly. We tried to take these realistic threats into account.”

There are three sections around acquiring the label, each contributing to the end goal by having a slightly different impact. The backbone of the technical requirements is the ETSI standard 303 645 – ‘Cyber security for consumer internet of things’. This standard has a total of 68 different provisions. “That’s quite a lot of things to consider when designing a product,” Vasenen added. “When we want to make sure that consumers are safe against realistic threats from the internet, only 18 of these provisions are required by the Finnish label.”

The selected 18 technical provisions are quite basic and include requirements such as a manufacturer should have a ‘public vulnerability disclosure policy’, ‘installation of updates should be secure’, ‘all unused interfaces must be disabled’, and ‘there should be no hard coded credentials in the system’.

The second key label requirement is that threat modelling must be performed on the product. There has to be some kind of list of threats that might be relevant to the product. “All the components, devices and systems in production are slightly different. So, we try to make sure that the realistic threats are identified by requiring threat modelling,” Vasenen continued.

The third element is basic security testing – all the threats that are identified in threat modelling need to be assessed within technical security testing. These are three very basic building blocks, and Vasenen added that the overall aim is not to have a huge list of individual requirements, but to make sure that the product is safe against the realistic threats.

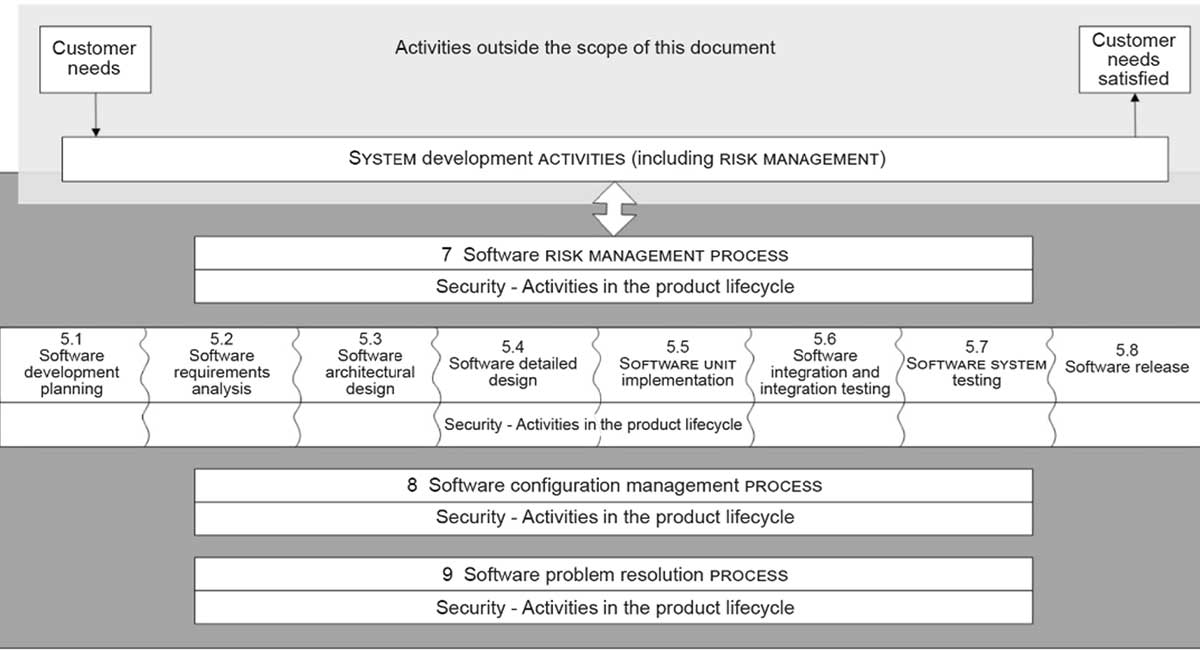

Cyber security label process

Added to this, Traficom has also tried to make the actual application process for the label simple. This is an eight-phase process that begins with initial discussions between Traficom, the manufacturer and, on occasions, the inspecting bodies. “During the initial discussions we make sure that we try to understand what kind of product we are dealing with – is the product a consumer IoT product? Is the product for the Finnish market or not, etc?”

Once these questions have been answered, the manufacturer then provides a statement of compliance, a product for the inspecting body, and will comment on whether the 18 technical requirements are met. When the inspecting body has a good knowledge of the product and the manufacturer believes it is compliant with the technical requirements, the inspecting body will create a threat model and a test plan, which Traficom will review.

Above: The cyber security label process

The inspecting body has a degree of freedom to choose how to perform the threat modelling, or what kind of test plan there should be. However, Traficom can review the threat model and test plan to make sure that the overall quality is on par with the expected levels. Also, approving the model and planning protects the manufacturers against excessive costs from the inspecting bodies. This also provides Traficom with a way to support the inspecting bodies in determining what is the desired depth of the testing.

The inspecting body then performs technical security testing and Traficom reviews the testing results and makes the decision to grant the label. If granted, all the information is published on the website, including the compliance of the statement.

Lessons

As mentioned earlier, in just under 18 months, the label has now been granted to nine different products with several more currently ongoing. One important lesson learnt by Traficom over this period is that, although the label was created for consumer IoT products, there is still an element of ambiguity in determining which products are suitable for the label and which are not.

The definition of a consumer IoT product is actually quite challenging. In the ETSI standard, which is used for the 18 technical requirements, they describe the consumer IoT device through multiple examples, such as IoT gateways, base stations, children’s toys, baby monitors, health trackers, smart watches, smart TVs and so on.

“In our view however, the label cannot be granted to a generic platform like a computer or a smartphone,” Vasenen commented. “Then there’s the question of whether a smart TV is a computing platform or an IoT product. A smart TV, for example, has an Android operating system, multiple network interfaces, and it can run apps.”

This means that defining label applicability in advance is a huge challenge. So far, Traficom’s solution has been to decide the applicability on a case-by-case basis within the initial discussions.

Another challenge has arisen through undefined methodologies. Traficom have been reluctant to force inspecting bodies to use certain frameworks or standards, and as such have offered a certain level of freedom for them to decide how to perform the threat modelling, what kind of test plan they want to create, and how they want to perform the technical testing.

However, this undefined methodology means that it can sometimes be difficult to communicate what is the desired depth and quality in all of those steps. “Our solution is to create more documentation, and have reports for the inspecting bodies that illustrate the depth and quality we expect,” continued Vasenen. “And then of course, there’s a huge challenge in the whole cyber security field, especially certification, as it’s constantly evolving.”

He added that while there seems to be numerous manufacturers who are interested, there is also a myriad of work being done around standardisation in various countries, and with these differing national efforts the sector is constantly evolving. And so, many companies appear to be waiting for the field to mature.

Key findings from the labelling process

The first and most obvious statistic that has emerged from Traficom’s labelling process so far is that not all products pass the cyber security evaluation. There have been numerous products turned down at various steps in the process – some at the first initial discussions, others during technical security testing, or on the 18 technical requirements.

“This is interesting because these manufacturers have previously stated that the product is compliant. However, the key point here is that there is no negative impact for the manufacturer. So, if a product fails the testing, there’s no penalty, and we don’t have a list of bad products.

“A good method in which to predict how a product is going to perform on security label testing is the overall security level of the manufacturer. And our impression is that if a manufacturer has well-established cyber security principles and processes, then their products tend to perform well.”

Evidence suggests thatif quality cyber security work is undertaken, then it passes through the entire company, from processes all the way to product development and design. One key takeaway is that when applying such a label, its crucial to have key personnel involved in the whole process.

He added that when trying to grant the label, if Traficom can only communicate with high level product management, there are many technical questions that may not get answered, which can lengthen the process considerably.

“One of our best experiences came from one small Finnish company,” Vasenen added. “We had daily discussions with the product development team, including electrical engineers, software engineers and product development teams. Whenever we had problems or questions regarding the product -didn’t understand how it worked; how it was supposed to operate; the rationale behind some of the functions etc, they were able to clarify the issues, often within minutes. And this was a huge factor in speeding up the process.”

Product cyber security is rooted in its basic functionality. Vasenen added that if we want to create products that pass cyber security evaluation, then it is important to have a security aware mindset and threat modelling throughout product development. Rely on well-known security functions and protocols, (don’t ever invent your own cryptographic functions). When using tools, make sure that the associated risks are understood, and that the tool is used correctly. It is all too easy to take a library and use that to perform encryption. But is the library being used correctly?

Don’t rely on security by obscurity – you should always assume that all product internals, even well protected secrets inside the product, will become public at some point, as the online community thrive from challenges and want to figure out how different kinds of devices work.

“Devices should be secure by default,” added Vasenen. “On too many occasions we have seen that the default settings on a device may be suitable only for a small portion of users. And these default settings might expand the attack surface unnecessarily.”

He added that technical depth should be avoided. This is the additional work that is needed to make a product technically sustainable in the long-term. It is accumulated by taking shortcuts in development, and when technical oversights are outdated and development practices are bad. Sometimes there might be a good reason to take technical depth if time to market is essential. But if there are weaknesses in the product, the online community will expose them.

Outsourced development and long supply chains can also lead to unknown product internals. So a situation may be created where technical development could be detached from product management, meaning the vendor contacts that tried to apply for the certification may not actually know how the device is working internally.

“When these basic building blocks are in order, it’s quite easy to make products that pass an evaluation,” Vasenen concluded. “To sum up, the Finnish cyber security label is a government backed label, and it’s a way to communicate to the consumer that a product fulfils certain requirements, is safe to use and is protected against threats from the internet.

“During the first year of providing this label, the reception has been very positive, and manufacturers are interested. Plus, consumers have shown that they trust the scheme. It’s straightforward, the process steps are minimal, the overheads are low, and the requirements are well-founded and easy to understand. It could be considered best practice for the whole industry.”