The European Commission (EC) has decided that the existing European Union (EU) Medical Device Directive (MDD) is not rigorous enough and it has been recast to a regulation – the Medical Device Regulation (MDR).

The difference between a directive and a regulation is that all member states in the EU are legally bound to abide to a regulation without any modifications (it enters law immediately) and that the EC can take measures to punish countries, manufacturers, importers, distributors or even individuals if it feels that any transgressions have been made and the local authorities have not been zealous enough in ensuring compliance. The wording used in a regulation is necessarily dictatorial.

The MDR will apply to all medical device manufacturers, meaning every manufacturer of a medical device or accessory will have new obligations. The MDR is probably unique in defining job descriptions of staff that must be employed by manufacturers if they wish to stay in the medical market and by giving the notified bodies extra duties to act as policing organisations, rather than just industry certification partners.

Innovation risk

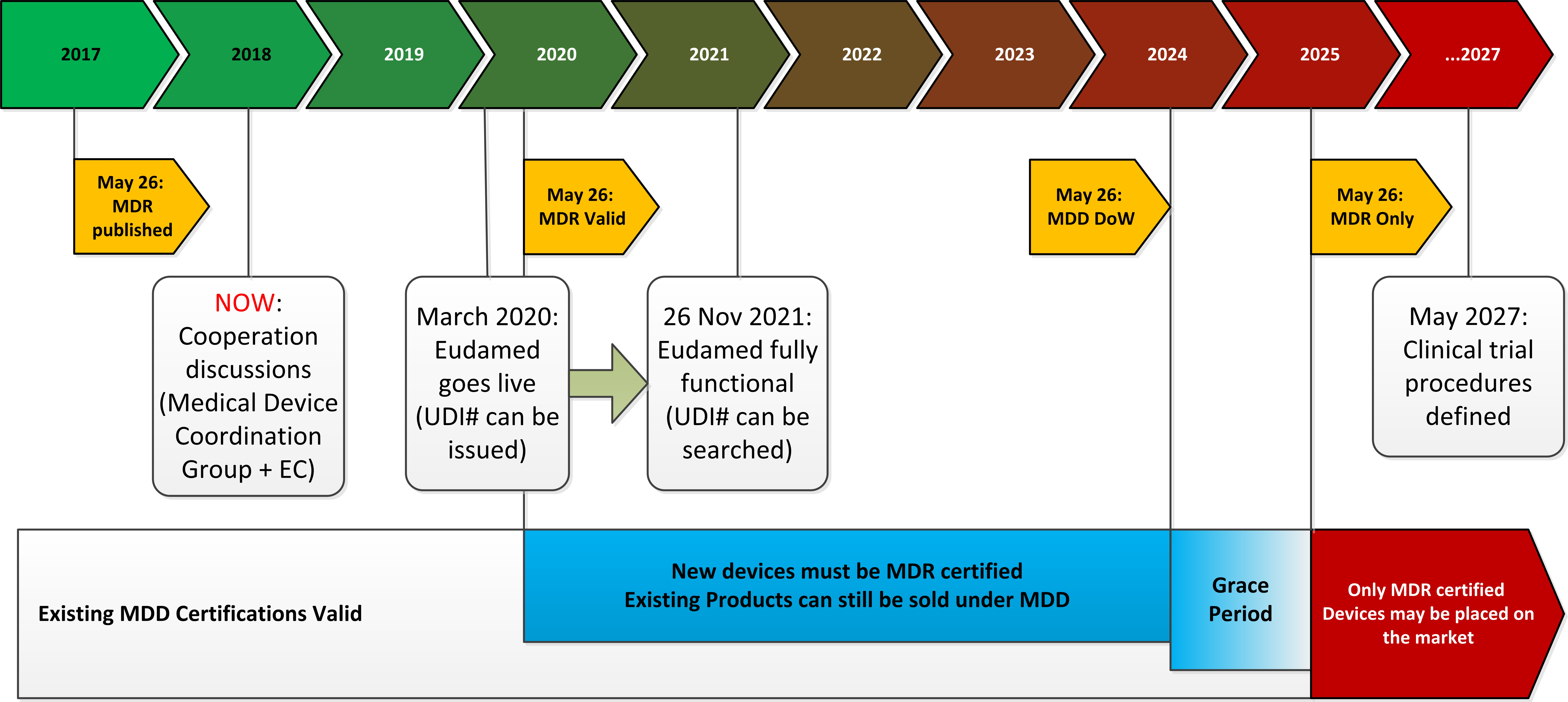

The MDR stretches to more than 300 pages in length and the publication date of the regulation was back in May 2017, giving manufacturers until 2020 to comply or they will lose the right to affix the CE mark for new products. Existing medical products on the market will automatically lose their CE mark four years after the application date of the new regulation, so there will be no so-called grandfathering option for existing medical products.

Figure 1: The timeline for transitioning from MDD to MDR

Figure 1: The timeline for transitioning from MDD to MDR

The introduction to the MDR states that it does not want to stifle innovation or business, but in reality the new requirements are so onerous that only original manufacturers are likely to be able to fulfil them. Importers and re-sellers who now simply brand label an OEM product will probably go out of business.

It is a clear intention of the MDR to raise the barriers to entry in order to impose tighter control over the distribution chain: “the own brand labeller has the regulatory responsibility as a manufacturer due to the fact that a brand is a symbolic representation of all the information connected to the product . . . from a consumer and patient safety perspective, own brand labellers should bear the regulatory responsibility of a manufacturer”.

The MDR is split into 10 chapters, each of which imposes new requirements that do not appear in the existing MDD.

Chapter 1 covers the scope and definitions. A new element is the inclusion of all medical-related devices. This even applies to groups of products without a current intended medical purpose but could be used in a medical environment, such as software, surgically implanted beauty products and diagnostic, prevention, monitoring, prediction, prognosis or treatment products. For example, a smartwatch that analyses the user’s ECG patterns will be now classed as a medical device, so will a contraceptive because it can be used to avoid the spread of disease. Medical software is now explicitly included, meaning that it must also be evaluated in a clinical environment.

Compliance

Chapter 2 covers the obligations of medical device suppliers. To meet the general safety and performance obligations, a clinical trial is almost always required. The onus is on the manufacturer to justify how they can demonstrate compliance if they do not carry out a clinical evaluation but the protocol of how that can be proved has not yet been worked out. Medical liability is extended to cover all “economic operators” including manufacturers, distributors, re-sellers and authorised representatives of foreign-made equipment. The MDR will require that all links in the distribution chain “have measures in place to provide sufficient financial coverage in respect of their potential liability”. In other words, even distributors will now need medical liability insurance cover.

Figure 2: Recom’s REM3.5E, REM5E and REM6E series of medical grade regulated DC/DC converters

Figure 2: Recom’s REM3.5E, REM5E and REM6E series of medical grade regulated DC/DC converters

Chapter 3 covers traceability. Every device, its associated distribution chain, test results and quality management (QM) documentation (including correspondence and detailed technical documentation, such as circuit diagrams and bill of materials) must be registered on a European databank called Eudamed. Once successfully registered, each device will be issued with a unique device identification (UDI) code that must be printed on the label. The documentation held on Eudamed will not be made publically available and only seen by the authorities but how this commercially sensitive information will be protected has not made clear.

Chapter 4 covers notified bodies (NBs). Each manufacturer must appoint a NB which will be responsible for policing the product during its entire working life by making unannounced audits and re-testing/re-certifying if it thinks fit. The EC reserves the right to scrutinise the checks carried out by the NBs and instruct other competent bodies to verify the results or demand extra information. The NBs rightly complain that this interferes with their professional practices and could cause additional delays with significant commercial disadvantages to the manufacturers. As of now, however, less than 30 institutions in Europe have applied for MDR accreditation; a drop of nearly half from the NBs currently accredited to certify for the MDD. There are simply not enough NBs with the resources available to implement the new regulation, so many products ready for market introduction will not get approval in time.

Chapter 5 covers classification. Each device will be classified according to purpose from Class I (the simplest) through Class IIA and IIB to Class III (the hardest classification, reserved for implants and other invasive applications). If it is not clear which class the product falls into, the EC is entitled to categorise and classify which products fall into the scope of the MDR themselves, if necessary overriding a decision made by a member state.

Chapter 6 covers clinical investigations. The manufacturer must provide clinical evidence to demonstrate compliance with the safety and performance and must plan, conduct and document a clinical evaluation which must be repeated at regular intervals throughout the lifetime of the product. This work will be overseen by a regulatory compliance manager which the manufacturer is required to appoint and who will be responsible for ensuring compliance. The regulation even includes a detailed job description of this post. It is allowed to use an outside consultant for compliance management, but the requirements for a continuously updated risk management and quality management (QM) system will be usually a full-time job.

Monitoring

Chapter 7 covers post-market surveillance. The manufacturer is responsible for carrying out periodic field investigations of the products put onto the market in order to collect data on the use, actual performance and to monitor any adverse events over the entire life-cycle of the product in order to carry out any necessary design improvements or field safety corrective actions. If a serious incident occurs during the lifetime of the product, the manufacturer must report this to the authorities.

Chapter 8 covers co-operation between monitoring bodies. An expert committee, the Medical Device Coordination Group (MDCG) will be responsible for overseeing the harmonisation of the MDR between member states.

Chapter 9 covers, amongst other things, penalties. “Member States should take all necessary measures to ensure that the provisions of this Regulation are implemented, including by laying down effective, proportionate and dissuasive penalties for their infringement.” There is no limit to the fines that could be issued for non-compliance.

Medical power

How would the MDR affect, for example, a manufacturer of medical grade power supplies?

A power supply is not a medical device in itself, so it falls outside of the scope of the MDR. However, it is a critical component of the overall medical device application, so there are a number of controls that apply to it.

For the Eudamed registration, the medical device manufacturer would have to rely on the supporting documentation delivered by the power supply manufacturer, including full disclosure of the technical, quality control, reliability and risk assessment documentations. For example, the information pack delivered by the manufacturer should include safety certifications (safety certificates, instruction manual, and appropriate use), EMC compliance (EMC certificates, assembly instructions, and test results), supply chain analysis (serial number, individual product test results and production bill of materials) and a communication exchange database (datasheets, e-mail correspondence and agreed specifications).

This information exchange is bi-directional. The medical device manufacturer is obliged to pass back down the chain any relevant feedback information on the end-usage including fault reports and any adverse events. As this process must be formalised, the majority of communication will be via questionnaires, Excel forms and checklists going back and forth in both directions. In practice, any end-customer making short run medical products could be overwhelmed by the extra paperwork.

On a technical level, the MDR requires that “Devices, where the safety of the patients depends on an internal power supply, shall be equipped with a means of determining the state of the power supply and an appropriate warning or indication if, or if necessary before, the capacity of the power supply becomes critical.”

Redesigning power

In practice, power supply manufacturers cannot assume that the safety of the patient is separate from the functioning of the power supply, so will need to integrate a “power supply ok” signal into the designs. This should detect any over-load, under-voltage, over-voltage or over-temperature conditions as all these factors could affect the performance of the power supply. It will also probably be necessary generate a warning signal to instruct the equipment to reduce the load if the power supply is getting close to its performance limit, so a simple LED power-on indicator will not be a sufficient method for compliance.

To fulfil this clause of the MDR means that almost every medical grade power supply product already on the market would need to be redesigned with sensors and a digital interface, thus eliminating around two thirds of existing power supply products on the market at a single stroke.

On a commercial level, the unannounced audits and re-testing that the NBs will be obliged to carry out will have to be paid for by the manufacturers. Probably only the larger medical companies will have the deep pockets needed to pay for the additional QM staff, unexpected audit charges and expert advice fees. The MDR states that the advice on compliance from the EC’s expert panel can be purchased. This will push up medical equipment prices as the end customer will need to pay for all of this new regulatory oversight. (On the other hand, if you are a NB or have a degree in QM and a few years’ clinical experience, you will be able to write your own pay cheque.)

There is, however a ray of hope in all of this doom and gloom. The MDR requires that every medical device is to be registered in a central European databank and given a UDI code. The EC already suspects that the Eudamed database will not be ready in time, it has allowed itself until 2025 to get the system up and running, which is five years after the MDR comes into force. This means that the smaller medical device manufacturers and distributors have been given a grace period after the withdrawal date of the MDD, up until May 2025 to clear inventory, thus giving them a little bit of extra income before they need to scrap products, close and hand over to the big EU multi-nationals, who will then have free rein over the medical device market.

Designing for the MDR

The following checklist may help manufacturers wanting to stay in the medical market after 2024:

1: If you are an importer or distributor, you will have the same responsibilities and liabilities as if you were a manufacturer. Unless you have direct contact with the original manufacturer with access to the design team, supply chain management and production, you will struggle to meet the regulatory requirements for traceability and post-market surveillance.

2: As a manufacturer of a component that in itself is not a medical device (e.g. a power supply), you will not be required to carry out clinical trials or apply for a unique identification code. However, you will still need to support and react to any adverse results arising from the use of the product inside the medical device over its lifetime. It is advisable to create a serial number for every product supplied, linked to full documentation (production testing results, quality control, bill of materials). A simple date code identifier will probably be insufficient.

3: If the supplied part has a potential hazard (electrical, thermal, sharp-edges, radiation), you will be required to carry out a risk assessment. This goes beyond the simple safety or EMC certifications, but will need to be an on-going and regular re-assessment. You will need to contact each and every customer who has purchased the product on a regular basis over the lifetime of the product. It would be advisable to enter into a contractual arrangement with customers to formalise this procedure.

4: There are not enough notified bodies (NBs) accredited to meet the requirements for the MDR. It can be that a new medical product may have a delayed market-entry because there is no NB available to take on the responsibility of monitoring it. Plan also for increased costs as demand outstrips supply.

5: Manufacturers will be required to have someone within the organisation responsible for regulatory compliance that possesses expert knowledge in the field of medical devices. If there is no such a specialist in-house, you will need to make arrangements with an external consultant.