Driver monitoring has moved from optional to critical, as vehicles increasingly rely on in-cabin vision to ensure safety. These systems detect drowsiness, distraction, and posture shifts that can compromise control, while also enabling smarter airbag and seatbelt responses. With imaging features and compact design, in-cabin cameras are fast becoming a standard in modern automotive safety.

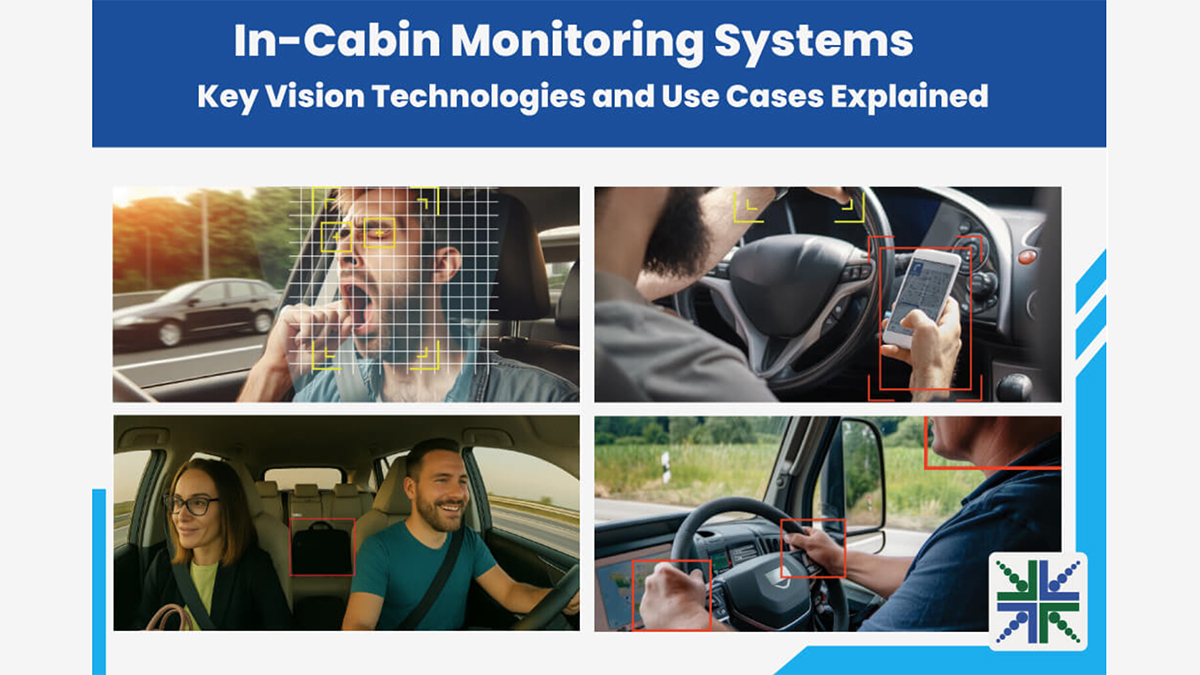

The reality is that driver-assistance systems are fast evolving. Hence, understanding what the driver is doing has become necessary for system response. That’s why cameras are placed inside the vehicle cabin – to be the primary source of this understanding. These embedded cameras track the driver’s eye movement, head position, facial orientation, and sometimes even hand gestures.

So, if a driver begins to nod off or glance away for extended periods, the system can trigger alerts, audio cues, or even adjust the vehicle’s response. If the driver fails to respond altogether, some vehicles initiate automatic braking or lane correction.

In this blog, you’ll understand more about how in-cabin monitoring cameras work through their primary use cases and learn about all the imaging features they need.

Use cases of in-cabin monitoring cameras

Drowsiness detection

Falling asleep while driving can lead to accidents within seconds. In-cabin monitoring cameras focus on eye behaviour, head tilt, and gaze fixation to detect these patterns early. The system builds a real-time profile of the driver’s alertness by measuring blink rate, eyelid closure, and duration of visual engagement.

Distracted driving

Looking away from the road can break attention loops. In-cabin cameras detect distraction by analysing head orientation, gaze direction, and upper-body movement. If the driver consistently turns away from the windshield or dashboard, the system responds with escalating alerts.

Object detection

Object detection systems distinguish between living occupants and inanimate objects. It becomes critical when seatbelts are triggered, airbags are deployed, or driver prompts are issued. Hence, cameras must help recognise shapes, textures, and reflectivity signatures.

Body posture

If a driver slouches, leans excessively, or turns to the rear, the system flags reduced driving control. For passengers, posture data contributes to accurate airbag deployment and seatbelt tensioning. Hence, cameras must interpret full-body behaviour in real time.

Top imaging features of in-cabin monitoring cameras

IR illumination and NIR sensitivity

Cabin lighting conditions can shift quickly, from bright daylight to dim evening commutes, making it hard to detect subtle cues like pupil movement or eyelid closure. Hence, in-cabin cameras rely on IR illumination. IR LEDs emit light invisible to the human eye but detected by NIR-sensitive sensors. This enables continuous observation across ambient light levels.

The in-cabin monitoring camera’s sensor must also have strong NIR sensitivity to accurately capture features such as pupils, eyebrows, and skin tone under IR illumination. It delivers stable, high-contrast imaging during night drives or in shadowed environments, while removing the need for mechanical filters that alternate between IR and RGB.

Wide field of view

The interior of a cabin is not a flat plane. The camera must capture facial expressions, head movements, hand gestures, and upper-body shifts: all from a fixed mount point. A narrow lens would miss critical parts of the scene, especially in large vehicles or flexible seating layouts.

A wide field of view (FoV) ensures that a single camera can observe the full driver region, and sometimes passenger areas as well. It increases system reliability while reducing the need for multiple cameras or moving mounts.

Global shutter

Drivers move and so do steering wheels, dashboard reflections, and handheld devices. In such environments, image capture must remain accurate even when the scene contains fast motion. Rolling shutter sensors may create skewed images under motion, which can mislead detection algorithms.

Global shutter sensors eliminate this issue by capturing the entire frame in a single instant. They help avoid motion blur, frame distortion, or geometric drift, especially important for eye tracking, gesture classification, and driver attention monitoring.

GMSL2 vs. MIPI interface

In-vehicle wiring must deal with EMI, space constraints, and long cable routing. Standard USB or ribbon interfaces struggle with these demands. GMSL2 (Gigabit Multimedia Serial Link 2) solves this by providing high-speed data transfer over coaxial cables up to 15 meters. It supports data, power, and control over a single line. It also enables seamless integration with NVIDIA Jetson-based platforms.

MIPI (Mobile Industry Processor Interface) fits a different niche. It works best for compact, standalone camera modules where the sensor sits close to the processor. Its direct, low-latency link makes it ideal for setups that prioritise speed over distance and when minimal delay and a small footprint are critical.

RGB-IR vs. monochrome

RGB-IR cameras capture both colour and infrared imagery, enabling in-cabin systems to maintain accurate driver and passenger monitoring in all lighting conditions. During the day, they provide detailed colour images, while at night they switch to infrared mode without the need for extra lighting adjustments.

Monochrome IR cameras, by contrast, are built solely for infrared capture, offering stronger low-light performance and higher contrast when colour data is unnecessary.

Mounting options

In-cabin cameras can be positioned in multiple locations to achieve optimal coverage. Windshield-mounted units give a broad, elevated view of both driver and passenger areas. Steering column-mounted cameras deliver a direct angle for precise tracking of eye and head movements. A-pillar-mounted cameras offer a side perspective that complements other viewpoints, improving overall monitoring accuracy.

The choice of mounting position depends on the vehicle’s interior layout, safety regulations, and desired field of view. In some deployments, multiple mounting points are combined to ensure redundancy and reduce blind spots.

Form factor

The cabin offers limited space for hardware. Cameras must fit inside tight enclosures, behind mirrors, in dashboards, or on the steering column. Large units block visibility or interfere with driver comfort. Size, weight, and mounting flexibility become critical design considerations.

Compact, lightweight camera modules with side, top, or rear exit connectors improve integration. Developers can also choose between bare-board versions for custom enclosures or enclosed versions for direct mounting.