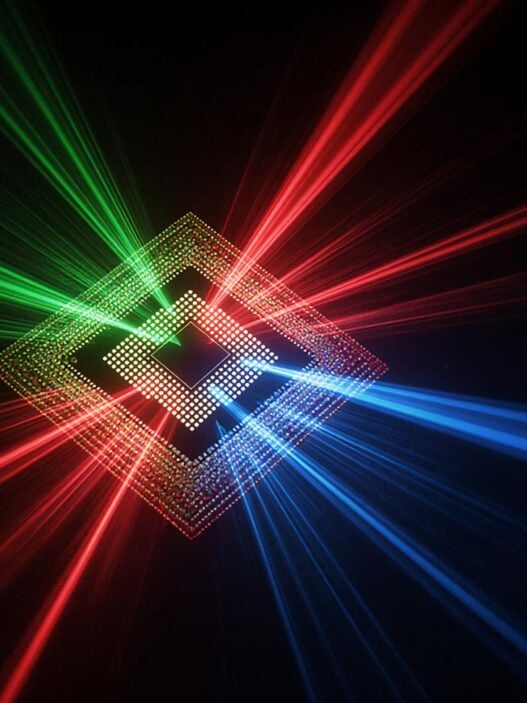

Researchers at the University of Glasgow have developed a laser-assisted nanofabrication technique that could enable a new generation of flexible, transparent electronic materials, potentially reshaping the manufacture of devices ranging from wearables to implantable medical sensors.

The approach, devised at the University’s Microelectronics Lab within the James Watt School of Engineering, allows ultra-thin metallic nanowires to be precisely patterned onto bendable polymer substrates without the need for costly cleanroom facilities. The team says the method could be scaled up for industrial production, overcoming longstanding constraints in nanomaterial manufacturing.

The process combines electric-field alignment with ultrafast laser engineering to create networks of silver nanowires on transparent polyimide films. These nanowires, around a thousand times thinner than a human hair, are arranged using a technique known as interfacial dielectrophoresis, which enables fine control over their orientation and geometry. In laboratory demonstrations, the researchers formed intricate patterns, including lettering, directly on the flexible substrate.

A key advantage of the material lies in its resistance to electromagnetic interference, an increasing challenge as wireless technologies such as 5G and wifi proliferate. Stray electromagnetic signals can disrupt sensitive electronics, particularly in medical devices. The Glasgow team’s nanowire networks incorporate nanoscale gaps that act as capacitors, reducing the penetration of external signals while maintaining electrical connectivity.

In a second manufacturing step, picosecond laser pulses are used to fuse the nanowire junctions and remove residual insulating coatings. This post-treatment improves optical transparency by up to 10% and reduces electrical resistance by a factor of 46, addressing the traditional trade-off between conductivity and transparency in metallic nanowire films.

Tests of prototype films showed shielding effectiveness of more than 35 decibels across frequencies from 2.2 to 6 GHz, blocking over 99.97% of incoming electromagnetic radiation, while retaining 83% optical transparency. The total thickness of the films is just over 5 micrometres.

Professor Hadi Heidari, who leads the Microelectronics Lab and is the paper’s corresponding author, said the work opened a new design route in nanotechnology by combining microelectronics with soft materials engineering. He added that the interference-shielding performance exceeded that of non-aligned nanowire materials by more than a thousand times, potentially enabling a wide range of flexible and implantable devices.

Beyond performance, the researchers emphasise manufacturability. Conventional cleanroom-based fabrication is typically restricted to small wafers and high costs. By contrast, the new method has already been demonstrated on sheets measuring 40 centimetres by 80 centimetres, with scope for further scaling.

Jungang Zhang, a Research Associate at the James Watt School of Engineering and lead author of the study, said the technique was the first to simultaneously improve conductivity and transparency in metallic nanowire networks. She noted that such properties were critical for flexible displays, wearable electronics, and implantable medical technologies, where reliable signal transmission must be combined with protection from electromagnetic noise.

The findings are published in ACS Nano, in a paper titled Laser-Engineered Interfacial-Dielectrophoresis Aligned Nanowire Networks for Transparent Electromagnetic Interference Shielding Films. The research was supported by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, part of UK Research and Innovation.