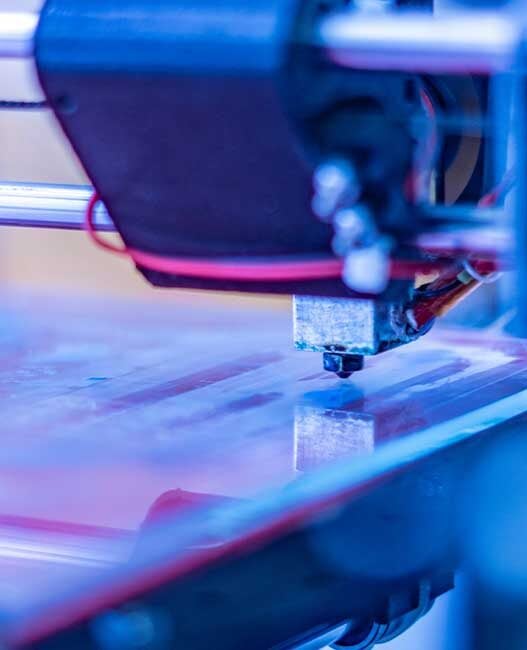

Researchers at EPFL have developed a new way to combine 3D printing with the growth of metals and ceramics inside a water-based gel. Their approach builds on vat photopolymerisation (VPP) but addresses the structural weaknesses that have limited the technique.

Rethinking vat photopolymerisation

Vat photopolymerisation is a form of additive manufacturing where a light-sensitive resin is poured into a vat and selectively hardened by a laser or UV light to create a solid structure. While it offers high precision, it is generally limited to polymers. Attempts to adapt it for tougher materials, such as metals or ceramics, have produced porous parts that tend to shrink or warp during processing.

Daryl Yee, Head of the Laboratory for the Chemistry of Materials and Manufacturing in EPFL’s School of Engineering, explained that these issues make existing VPP-based metal or ceramic parts structurally unreliable.

Building strength with hydrogels

Yee and his team set out to overcome these challenges by separating the printing step from the material-forming step. Instead of hardening a resin containing metal precursors, they first 3D print a scaffold from a simple water-based hydrogel. This printed structure defines the final shape but acts only as a temporary framework.

The researchers then infuse this ‘blank’ hydrogel with metal salts, which are chemically converted into nanoparticles that spread throughout the gel’s structure. Repeating this infusion and conversion cycle several times increases the metal concentration. After five to ten cycles, the hydrogel is burned away, leaving behind a dense metal or ceramic object that retains the geometry of the original 3D print.

Yee describes the approach as a low-cost way to produce high-quality metals and ceramics while introducing a “new paradigm in additive manufacturing” – where material selection takes place after 3D printing, rather than before.

Testing complex geometries

To demonstrate the versatility of their technique, the EPFL team fabricated intricate lattice structures known as gyroids using iron, silver, and copper. These geometries were chosen for their complexity and mechanical testing potential.

When tested using a universal testing machine, the new materials withstood 20 times more pressure than parts produced by previous polymer-to-metal conversion methods. They also showed a much lower shrinkage rate of around 20%, compared with 60-90% for earlier techniques.

Future applications and improvements

The researchers believe their method could be valuable for manufacturing strong yet lightweight 3D architectures, including sensors, biomedical devices, and components for energy conversion or storage. Metals with high surface areas could also serve in catalytic or cooling applications for energy technologies.

Looking ahead, the EPFL team plans to further improve the density of their materials and automate the infusion process to make it faster. According to Yee, a robotic system could help reduce processing time, making the technique more practical for industrial adoption.