As of March 2024, there were approximately 11,800 data centres worldwide, according to Visual Capitalist, and this number has continued to grow since then. PwC predicts that the global data centre market is projected to reach $1 trillion by 2027, which shows the scale of growth that is expected.

However, data centres are using a concerning amount of water. Data centres rank among the top ten most water-intensive commercial sectors, so the link between data infrastructure and environmental impact has become a pressing international concern.

As sustainability climbs in importance when it comes to AI and the environmental impacts it is having, unconventional solutions are being suggested. One of these has been the idea that data centres could heat swimming pools to reduce energy costs by using the heat they generate, and a new suggestion has been introduced by water company Anglian Water.

Anglian Water believes that data centres should be cooled using “treated sewage effluent”, rather than using fresh drinking water. For this to work, data centres should be located near water recycling plants in order to have easy access to the coolant they need.

According to the Environment Agency’s (EA) National Framework for Water Resources, published on 17 June 2025, England’s public water supply could be short by five billion litres a day by 2055 without urgent action to futureproof resources. According to the press release that was released in conjunction with the report, “the EA wants businesses to explore more options for using non-potable water – perfectly usable but not for human consumption.”

The government has pledged to expand AI infrastructure nationwide and opened the floor for regions to bid for “AI growth zone” status with Culham in Oxfordshire first in line. But there is a catch: Each application needs to be backed by a letter of support from the local water supplier, signalling that the area’s resources can shoulder the load of advanced computing.

As reported by the BBC, Geoff Darch, Head of Strategic Asset Planning at Anglian Water, has said that the company has received “expressions of interest for AI growth zones, but also for specific data centres.”

But has also said that if a developer approached the company asking for a tap water connection for a large data centre in a water-stressed part of the region it covers, that it would be “challenging”.

The BBC quoted Darch, explaining the alternative sources of water for the job: “It’s possible we won’t need to use drinking water to cool these facilities. We could use things like treated sewage effluent, that could be equally good to cool these data centres.”

Data centres and hydrogen production are expected to become two major sources of industrial demand for water in the future. Although these sectors might represent only single-digit percentages of Anglian Water’s total supply, this could still amount to tens of millions of litres of water per day. Looking at other options, like sewage, can take the strain off the demand for drinkable tap water by a significant amount, especially in water scarce areas.

Darch finished explaining that the supply and demand for water has become increasingly tight, and that “we’ve got to start thinking more in a kind of scarcity mindset.”

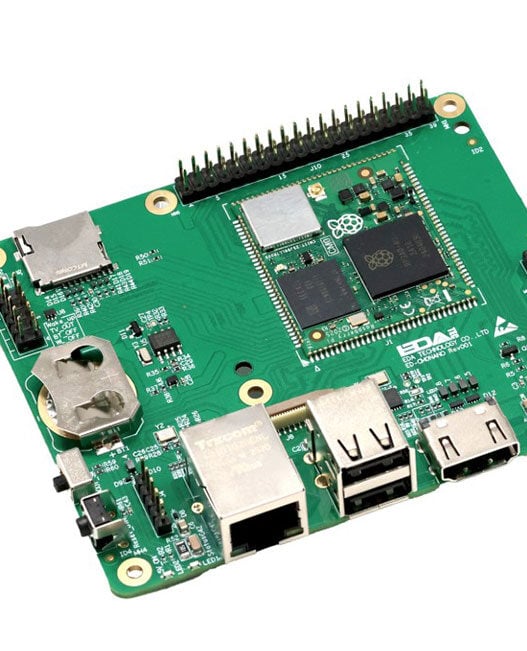

Data centres gained “critical national infrastructure” status in September, putting them on the list for priority government support during major incidents – whether facing a cyber attack, system outage, or extreme weather event – to help keep operations running and disruption low.

John Booth, Chair of the Data Centre Alliance’s energy efficiency and standards committee, told the BBC he “would not see a problem” with using “pumped effluent from the very last stage of a sewage plant” for cooling. He noted that the water would be treated on-site before entering the cooling system.

However, he suggested that concerns about water use in data centres stemmed largely from the consumption patterns of US facilities.

In the US, most data centres rely on “evaporative cooling” – a system that sprayed water onto heat exchangers, tailored for conditions hitting 28°C and above. By contrast, large-scale UK sites operate with “closed loop” cooling systems, which run without the need for a constant water supply.

The statistics for how much water UK data centres use aren’t widely available, so the estimate for how much water could be saved by using treated sewage isn’t currently known. However, any new innovation that can save and decrease the use of natural resources when alternatives are available should always be considered.