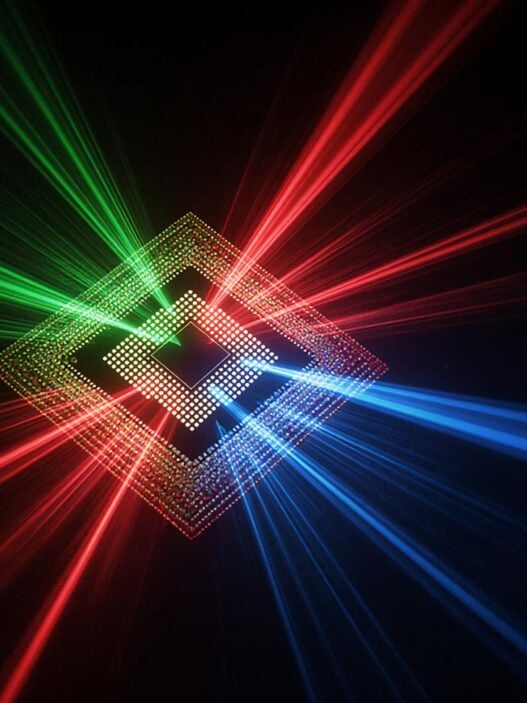

This shift toward light-based, or optical, computing hinges on developing new components that can manipulate light in ways that conventional electronics cannot.

Engineers at the John and Marcia Price College of Engineering have taken a step in that direction with the development of a new device that can dynamically control the circular polarisation of light. This chiral property – essentially the ‘twist’ of light – can be used to encode and store information, offering a pathway to more compact and efficient optical circuits.

The work was led by Assistant Professor Weilu Gao of the Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering, and PhD candidate Jichao Fan. Their findings were published in Nature Communications, with contributions from Gao lab members Ruiyang Chen, Minhan Lou, Haoyu Xie, Benjamin Hillam, Jacques Doumani, and Yingheng Tang, as well as Nina Hong from the J.A. Woollam Company.

Gao explained the limitations of conventional chiral optics: “Traditional chiral optics were like carved stone – beautiful but frozen,” he said. “This made them not useful for applications requiring real-time control, like reconfigurable optical computing or adaptive sensors.”

In contrast, the new device – described by Fan as “‘living’ optical matter” – responds in real time to electrical pulses.

“We’ve created ‘living’ optical matter that evolves with electrical pulses,” said Fan, “thanks to our aligned-carbon-nanotube-phase-change-material heterostructure that merges light manipulation and memory into a single scalable platform.”

The heart of the device is a carefully engineered heterostructure composed of multiple stacked thin films. Among them is a layer of carbon nanotubes aligned in varying directions, serving dual functions: manipulating light’s chirality and conducting electrical signals. These signals trigger a phase-change material (PCM) layer – specifically GST – to transition between amorphous and crystalline states via heat.

“The carbon nanotubes simultaneously act as chiral optical elements and transparent electrodes for PCM switching – eliminating the need for separate control components,” said Fan.

This structural change affects the material’s circular dichroism – the degree to which it absorbs left- or right-circularly polarised light. The researchers could finely control this property across a full wafer thanks to improvements in the scalable fabrication of both the aligned carbon nanotubes and the PCM layers.

Once integrated, the heterostructure selectively filters circularly polarised light depending on the state of the PCM. Crucially, this process is reversible and electrically tuneable, allowing real-time control over the device’s optical behaviour. That opens the door to encoding information based on the ‘handedness’ of polarised light, potentially creating new channels for optical memory and computation.

“By adding circular dichroism as an independent parameter, we create an orthogonal information channel,” said Gao. “Adjusting it does not interfere with other properties like amplitude or wavelength.”

As researchers continue to push the boundaries of optical computing, devices like this could become fundamental components – unlocking new ways to process information at the speed of light.