According to research conducted by Graphite, AI-generated articles have already surpassed the volume of human-written content online. The finding is based on an analysis of 65,000 English-language URLs published between January 2020 and May of this year, drawn from the Common Crawl archive.

Experts warn that AI-generated content may make up as much as 90% of online material as soon as next year, raising concerns about quality and the risks of models learning from AI-produced text. This rapid shift is forcing educational institutions to rethink how generative tools fit into learning and assessment, leading to responses that range from strict bans to conditional use and active integration.

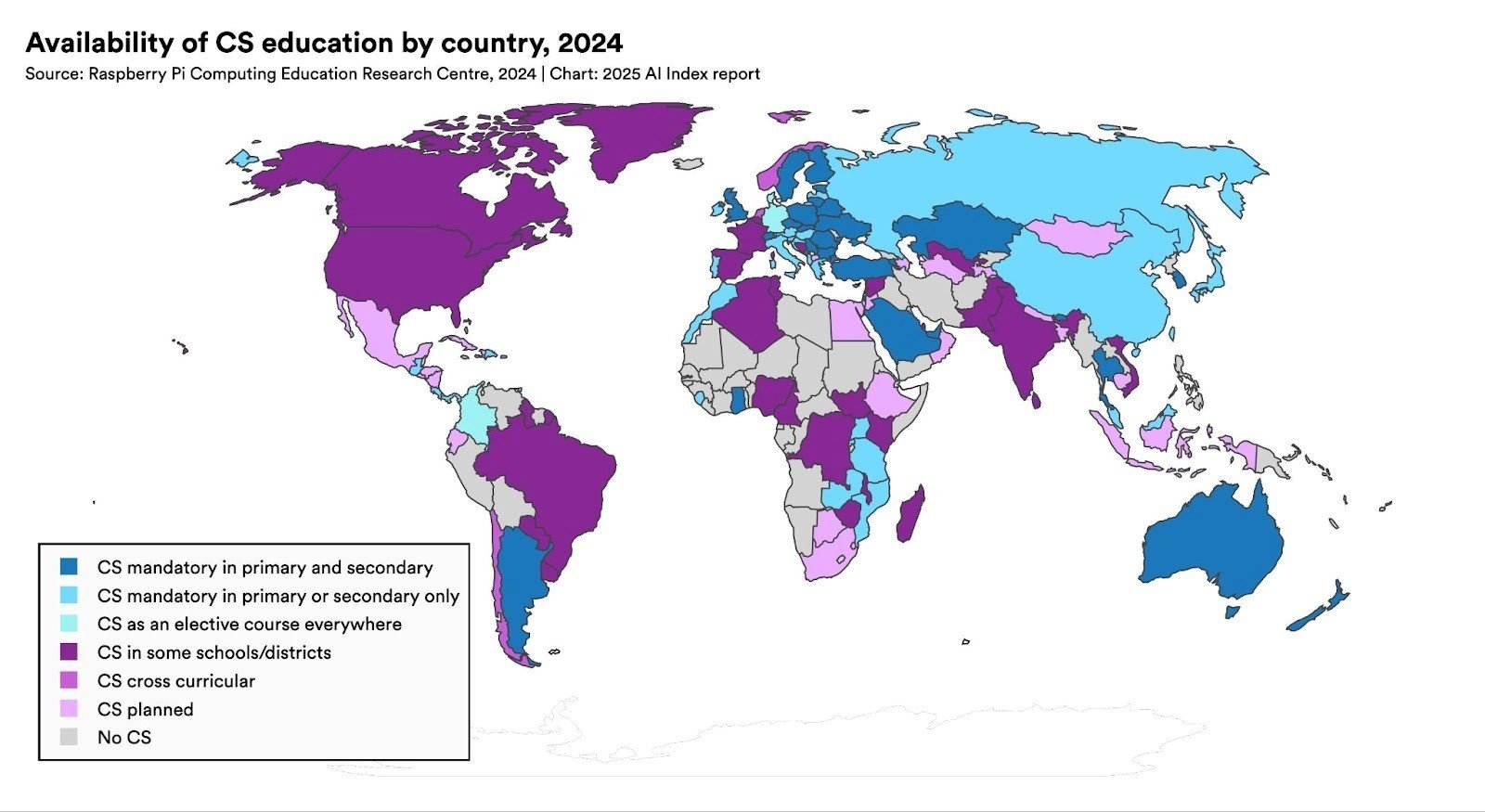

The 2025 AI Index Report shows that AI and computer science education are growing worldwide, but major gaps persist. Many countries are expanding K–12 CS access, and US computing graduates have increased, yet infrastructure shortages and limited school offerings, both globally and in the US underscore how unevenly education systems are prepared for accelerating AI.

What accounts for the emerging gap between US and European approaches to AI in education?

In the European Union, regulation is notably stringent. The EU AI Act, which entered into force on 1st August 2024 and is being phased in until 2nd August 2027, establishes a risk-based regulatory scheme for AI systems. This designation requires continuous risk assessment, technical documentation, and human oversight. For Generative AI systems, the Act mandates transparency, including disclosure of AI-generated content and safeguards against harmful output. It also prohibits certain practices outright, such as emotion recognition in schools and biometric social scoring.

In contrast, the United States maintains a more flexible and decentralised environment. With no federal equivalent to the EU AI Act, universities develop their own policies, creating a landscape of varied approaches. Some institutions emphasise transparency and attribution, while others allow wide latitude for experimentation under academic freedom.

As EU requirements expand, students and faculty must navigate increasingly complex expectations. Stricter compliance may restrict access to certain tools or slow adoption, raising concerns about consistency and potential inequities across institutions.

Implications for students and faculty: confusion, uneven access, and growing trust gaps

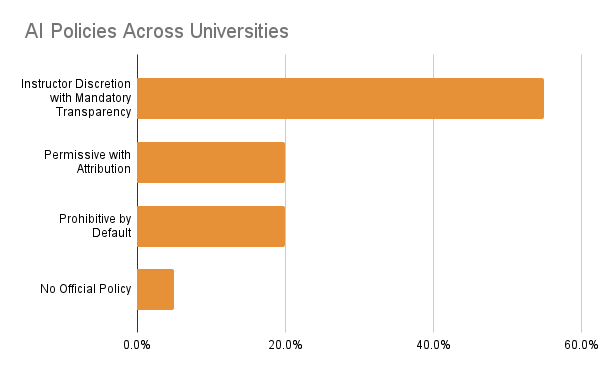

As the gap between US and European approaches grows, students face inconsistent rules while faculty work to reconcile institutional autonomy with emerging regulatory demands. To illustrate how fragmented this landscape is, researchers group universities into four categories.

The first and largest – Instructor Discretion with Mandatory Transparency (55%) – requires students to disclose any AI use while leaving specific rules to individual instructors, as seen at Harvard. This creates a course-by-course patchwork that many students describe as confusing to navigate. The second – Permissive with Attribution (20%) – includes institutions like Oxford and Yale, where AI is openly allowed as long as its use is acknowledged. The third – Prohibitive by Default (20%) – bans Generative AI unless explicitly authorised, sometimes imposing strict penalties. Finally, a small group – No Official Policy (5%) – still provides no formal guidance, leaving students to rely on older academic integrity codes not designed for the AI era.

The growing inconsistency of AI policies has created a confusing learning environment where students encounter conflicting expectations and hesitate to use legitimate tools. Faculty face similar uncertainty, often lacking clear guidance on how to integrate or regulate AI.

This instability is eroding trust in the classroom. Many instructors report increased scepticism toward student work, while students describe rising anxiety and reluctance to write confidently or collaborate, worried that normal academic behaviour might be misinterpreted.

Amid these pressures, evaluations of AI-supported grading tools suggest that more consistent assessment could help reduce uncertainty. In one benchmark, an early AI-assisted system differed from human graders by only 0.2 GPA points across 60 essays and delivered stable, rubric-based feedback. These tools cannot resolve policy fragmentation, but they illustrate how transparent and explainable evaluation methods may offer stability at a time when unclear rules, growing enforcement demands, and rising institutional costs strain both students and faculty.

Meanwhile, the institutional cost of AI enforcement has escalated dramatically. Investigating a single suspected AI case requires more than 160 minutes of combined staff time, and universities processing hundreds or thousands of cases each year face tens of thousands of hours diverted from teaching and support. UK institutions now spend an estimated £12.4 million annually on AI-related misconduct enforcement alone, with US costs projected at nearly $200 million. Some universities have seen integrity cases rise more than 400%, underscoring how unclear policies and reactive enforcement are straining resources and shifting attention away from education itself.

What do top universities’ policies look like?

Across several top institutions listed in the Times Higher Education World University Rankings 2026, a review of AI policies reveals consistent patterns. Common themes such as transparency, instructor-level discretion, and controlled experimentation regularly appear in how these universities articulate and implement their approaches to Generative AI.

As we found, Oxford and ETH Zurich exemplify an open-but-structured approach. At Oxford, students are permitted to use generative AI tools to support their learning, provided they critically assess and properly attribute any AI-generated material; undisclosed use in assessed work is treated under the university’s plagiarism regulations.

Meanwhile, ETH Zurich explicitly encourages the use of GenAI in teaching and research but requires transparent declaration of usage, adherence to the principles of responsibility, fairness, and academic integrity, and includes a formal ‘declaration of originality’ that must note if AI was used.

By contrast, Harvard and Columbia rely heavily on instructor discretion. At Harvard, faculty are urged to define their own generative-AI policies in course syllabi, some may ban tools entirely, others may encourage their exploration, but disclosure is always required.

At Columbia, the Office of the Provost states that Generative AI may not be used in assignments or exams unless explicitly permitted by the instructor; unauthorised use is considered akin to plagiarism.

A third pattern can be seen in technical and research-focused universities like Stanford and MIT, which actively promote experimental and pedagogically guided adoption. Stanford, for example, provides a dedicated ‘AI Playground’ and recommends that instructors design assignments that balance AI use with disclosure, human oversight, and learning objectives.

MIT, similarly, supports responsible AI deployment through hubs and research initiatives (such as RAISE and Open Learning projects), helping both students and faculty build AI literacy and reflection capacity, not simply banning or ignoring generative tools.

Why harmonising approaches and not expanding bans matters most?

Taken together, these cases illustrate that rigid restrictions alone cannot address the pace at which Generative AI is reshaping academic work. As universities adopt increasingly divergent policies, the risks of inconsistency, misinterpretation, and unequal access only intensify.

Harmonising core principles provides a more stable foundation than outright prohibition. Equally important is the development of AI literacy: equipping students and faculty to understand, interrogate, and appropriately integrate these systems. In a landscape defined by rapid technological change, shared norms and informed practice offer far greater resilience than bans that quickly become outdated.