While machine learning continues to stimulate conversation in the world of computing, a far more profound breakthrough may be unfolding at temperatures verging on absolute zero.

Here, the conventional ones and zeros of binary code give way to the enigmatic realm of quantum states, ushering in a revolutionary approach to computation, one capable of tackling problems that were once deemed unsolvable. In the rapidly evolving universe of quantum computing, it seems that being cold is, in fact, incredibly hot.

The quantum quotient

At the heart of quantum computing lies the qubit, or ‘quantum bit,’ which can exist in every possible state simultaneously until it is observed. Only then does it crystallise into a definitive 0 or 1. While this peculiar property may seem trivial for a lone qubit, the true power of quantum computing emerges when multiple qubits become entangled. In this mysterious phenomenon, what Einstein described as “spooky action at a distance”, the states of two or more entangled qubits become interconnected, irrespective of the distance between them, enabling the collective system to represent every combination of their individual states at once. Quantum gates, the operational workhorses of such machines, enable computations to occur across this multitude of entangled qubits simultaneously. When the quantum system is finally measured, the multiple probabilities collapse into a single, concrete result, delivering definitive answers unlike anything achievable with traditional computers.

Building better quantum computers and satellites

Creating the next generation of quantum computers isn’t easy. The central obstacle is in the delicate task of setting, preserving, manipulating, and ultimately reading out the astonishingly fragile quantum states that drive these machines. The slightest judder of mechanical vibration, a hint of thermal fluctuation, or a stray electrical or electromagnetic disturbance can send these states into disarray, wiping out irreplaceable calculations in an instant. To shield their computations from this relentless barrage of interference, researchers are pushing quantum hardware to operate at temperatures of -273.15ºC, all but indistinguishable from absolute zero.

Some machines rely on radio-frequency (RF) signals to configure quantum states and extract results by painstakingly capturing the faint emissions from qubits. Achieving this level of precision requires RF circuits, connectors, and cabling engineered to ruthlessly suppress signal loss, noise, and interference, ensuring that even the tiniest quantum emissions are heard distinctly and clearly.

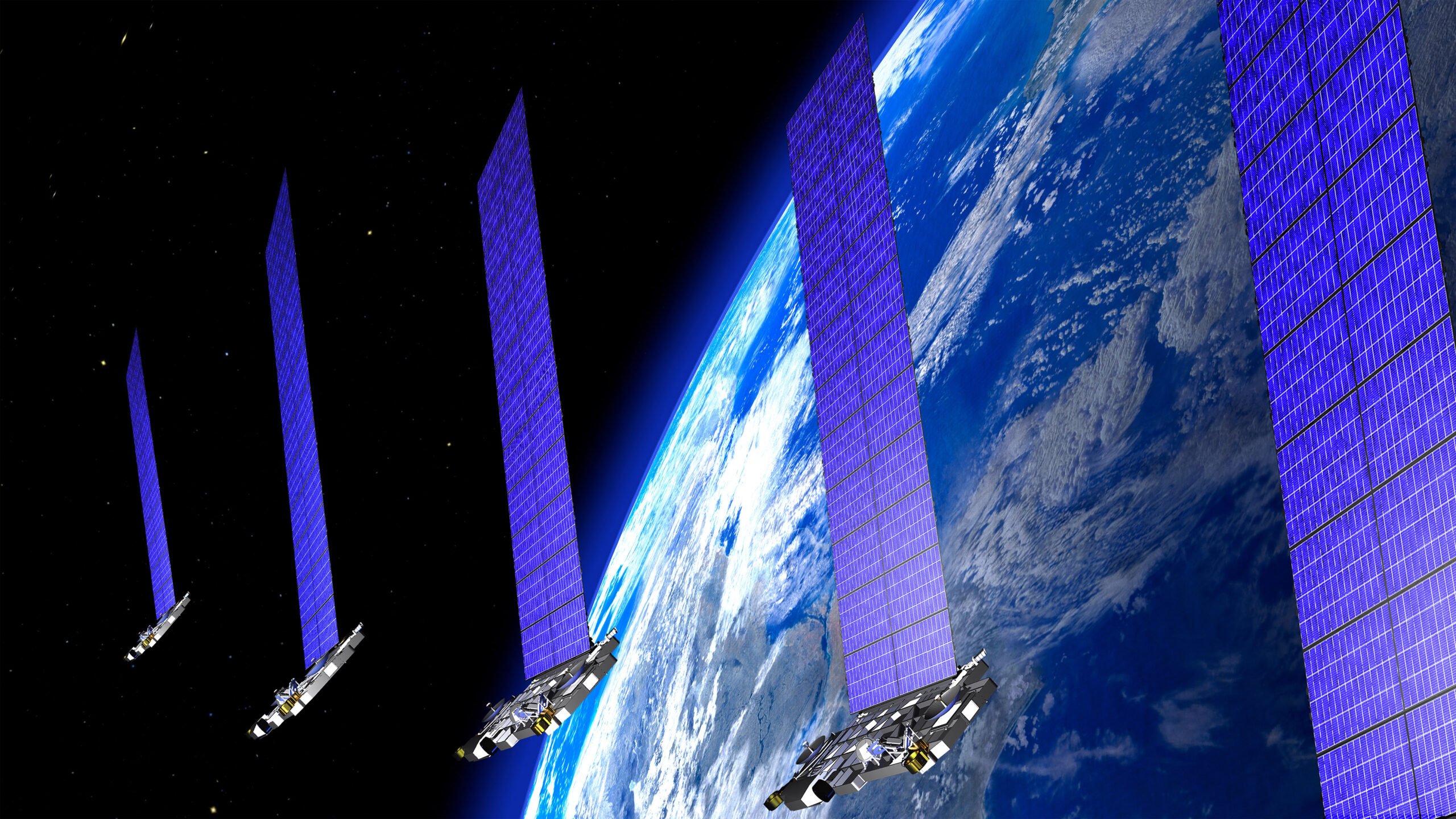

Satellite technology grapples with similar challenges, despite operating at temperatures ranging from -65 up to +125 ºC for low-Earth-orbit networks. Within these space-borne platforms, radio-frequency switching plays a pivotal role in seamlessly directing transmit and receive signals, enabling satellites to not only maintain reliable communications but swiftly redirect operations to backup hardware or dynamically adjust their payload configurations.

In satellite systems, RF switching falls to a lineup of high-reliability devices, ranging from robust mechanical switches to advanced semiconductor and microelectromechanical (MEMS) technologies. Each of these components must contend with relentless cycles of heating and cooling, the challenge of managing significant power loads, the need to preserve package integrity amid the stresses of orbit, and above all, an imperative for unwavering reliability. Semiconductor switches must also withstand the persistent assault of cosmic radiation, which gradually erode or abruptly compromise their switching functionality, putting the entire system at risk.

The MEMS alternative

Microelectromechanical systems, or MEMS, have made their mark in everyday technology, powering smartphones, airbag sensors, and vehicle navigation systems. Built using adaptations of conventional integrated circuit manufacturing techniques, they are becoming increasingly ubiquitous.

MEMS switches are constructed around a metal beam, outfitted with a contact that hovers above, but remains separated by air from, a matching contact below. Activation comes via an electrostatic field applied to electrodes flanking the mechanism, causing the metal beam to bend down and contact its counterpart. This architecture delivers highly linear signal transmission, even at millimeter-wave frequencies. Insertion loss is minimal. Switching occurs in microseconds, offering rapid response times, and such devices can handle high voltages when configured in parallel.

Menlo Micro of Irvine, California, which has advanced research originally pioneered at GE, has focused on refining the materials at the heart of MEMS switching. Their efforts yielded an electro-deposited alloy that is engineered to mirror the mechanical resilience of silicon while preserving the exceptional electrical conductivity of metal.

Menlo partnered with glass industry leader Corning to develop a specialized glass substrate on which to plate the MEMS switches. Additionally, it’s partnership with Samtec to develop hermetic through-glass via (TGV) connection technology not only streamlines internal wiring, eliminating the bottlenecks that often hamper high-frequency operation, but helps to maintain an airtight hermetic seal. This ensures the delicate metal beam mechanism and contacts is shielded from the damaging effects of moisture and other contaminants, ensuring long-term reliability in even the harshest environments.

MEMS in the cold

As quantum computing and satellite engineering push the boundaries of what’s possible, reliable, high-performance switching at cryogenic temperatures has researchers rigorously investigating how different switch technologies behave under such frigid conditions.

A joint effort by the National Institute of Standards and Technology and the University of Colorado at Boulder has already demonstrated that MEMS switches continue to function and operate robustly at cryogenic temperatures at and below 18 Kelvin, maintaining operability throughout a grueling test of one million switching cycles. The switches’ contact resistances were so low that every device remained operational. Menlo asserts that its MEMS-based switches can tolerate up to 3 billion cycles at room temperature before reaching end of life.

The MEMS advantage: a strong contender for quantum computing

Quantum computing stands as perhaps the most transformative technology innovation this decade. But achieving its full potential requires careful evaluation of every possible architecture and component, weighing each for its likelihood to contribute meaningfully before converging on a final design. In this high-stakes selection process, MEMS-based switches are emerging as the high-performing and robust candidates, especially as their reliability at cryogenic temperatures continues to be validated. When one examines the evidence with a clear eye, MEMS switches are poised not just to compete, but to take centre stage as the preferred switching solution for the next wave of quantum computers.