Researchers at Michigan State University have discovered how to use a fast laser to wiggle atoms in a way that temporarily changes the behaviour of their host material. Their novel approach could lead to smaller, and more efficient electronics – such as smartphones – in the future.

Tyler Cocker, an associate professor in the College of Natural Science, and Jose L. Mendoza-Cortes, an assistant professor in the colleges of Engineering and Natural Science, have combined the experimental and theoretical sides of quantum mechanics — the study of the strange ways atoms behave at a very small scale — to push the boundaries of what materials can do to improve electronic technologies we use every day.

“This experience has been a reminder of what science is really like because we found materials that are working in ways that we didn’t expect,” explained Cocker. “Now, we want to look at something that is going to be technologically interesting for people in the future.”

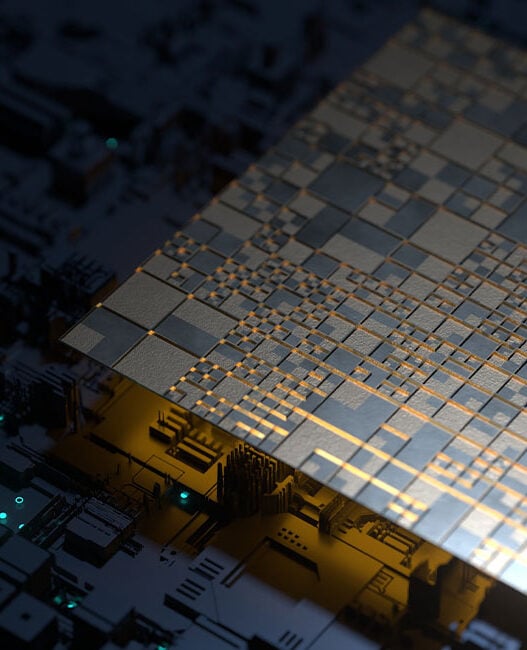

Utilising a material called tungsten ditelluride, or WTe2,which is made up of a layer of tungsten, or W atoms, sandwiched between two layers of tellurium, or Te atoms, Cocker’s team carried out a series of experiments where they placed this material under a specialised microscope they built.

While microscopes are typically used to look at things that are hard for the human eye to see, like individual cells, Cocker’s scanning tunneling microscope can show individual atoms on the surface of a material. It does this by moving an extremely sharp metal tip over the surface, ‘feeling’ atoms through an electrical signal, like reading braille.

While looking at the atoms on the surface of WTe2, Cocker and his team used a super-fast laser to create terahertz pulses of light that were moving at speeds of hundreds of trillions of times per second. These terahertz pulses were focused onto the tip. At the tip, the strength of the pulses was increased enormously, enabling the researchers to wiggle the top layer of atoms directly beneath the tip and gently nudge that layer out of alignment from the remaining layers underneath it. Imagine it as a stack of papers with the top sheet slightly crooked.

While the laser pulses illuminated the tip and WTe2, the top layer of the material behaved differently, demonstrating new electronic properties not observed when the laser was turned off. Cocker and his team realised the terahertz pulses together with the tip could be used like a nanoscale switch to temporarily change the electrical properties of WTe2 to upscale the next generation of devices. Cocker’s microscope could even see the atoms moving during this process and photograph the unique ‘on’ and ‘off’ states of the switch they had created.

When Cocker and Mendoza-Cortes realised that they were working on similar projects from different perspectives, Cocker’s experimental side joined with Mendoza’s theoretical side of quantum mechanics. Mendoza-Cortes’ research focuses on creating computer simulations. By comparing the results of Mendoza’s quantum calculations to Cocker’s experiments, both labs yielded the same results — independently and by using different tools.