The US Department of Agriculture estimated that between 30 and 40% of the nation’s food supply goes to waste each year. This adds up to billions of pounds discarded in landfills, releasing methane and carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. Alongside this, concern continues to grow over plastic pollution, with microplastics from bags and bottles finding their way into water supplies and the human body.

Researchers at Binghamton University believe part of the answer could lie in tackling both challenges at once. A team from the Thomas J. Watson College of Engineering and Applied Science’s Department of Biomedical Engineering investigated how food waste could be converted into biodegradable plastic, offering insights that could support future industrial-scale applications. Their findings were published in the journal Bioresource Technology.

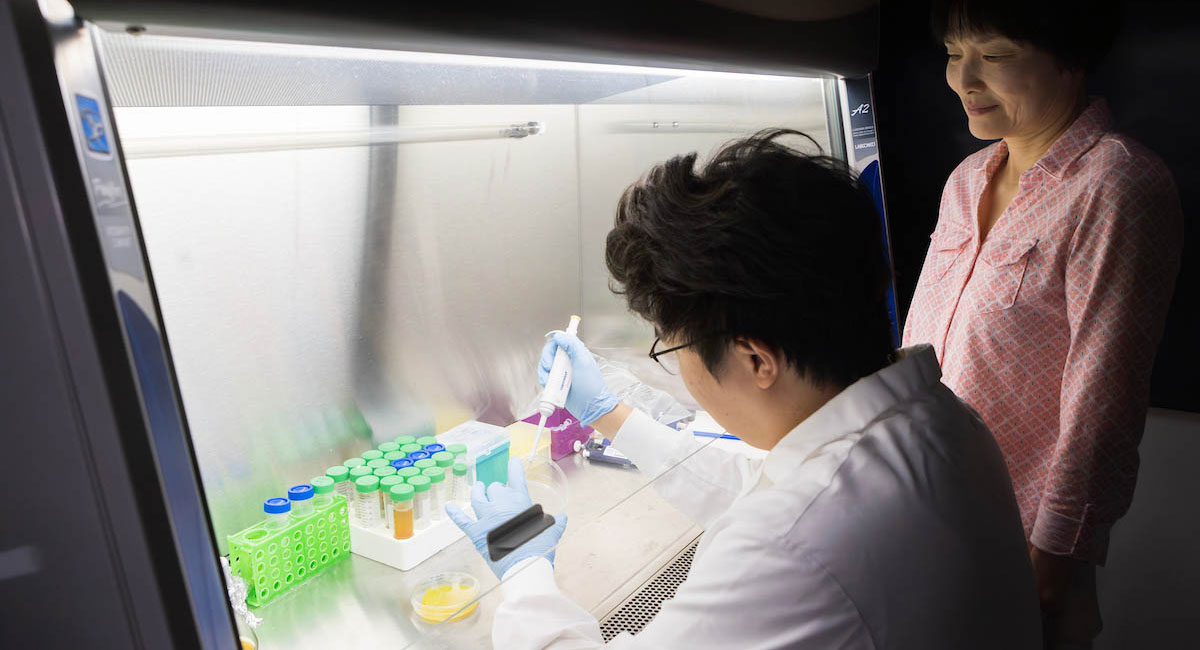

The project was led by PhD candidate Tianzheng Liu, with faculty support from Professor Sha Jin and SUNY Distinguished Professor and Chair, Kaiming Ye.

“Bioresource Technology is a high-quality journal, so being published quickly speaks to the importance of this research,” Jin said. “The reviewers commented that ‘the manuscript demonstrates significant scientific merit, novelty and environmental relevance.’”

Jin’s interest in food waste stemmed from a New York state grant awarded in 2022.

“We can utilise food waste as a resource to convert into so many industrial products, and biodegradable polymer is just one of them,” she said. “We’re aiming not only to valorise food waste but also reduce manufacturing cost of this ecofriendly polymer. There are also different options, like generating biofuels and biochemicals.”

Current biodegradable plastic production relies on refined sugar substrates and pure cultures of microorganisms, making it costly. To address this, the Binghamton team used food waste fermented into lactic acid as a carbon source, alongside ammonium sulfate as a nitrogen source, to feed Cupriavidus necator bacteria. The bacteria produced polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA), a bioplastic that can be harvested for packaging and other uses. About 90% of the PHA created by the bacteria can be collected.

For Liu, the project was a departure from his previous focus on stem cell research.

“The bioconversion of food waste into organic acids was a relatively easy one. Cultivation of the plastic-producing bacteria was hard, because at the beginning I didn’t have experience with bacteria fermentation for producing biopolymer,” he said. “At every move, I felt like something was not what I expected.”

The food waste used for experiments came from Binghamton University Dining Services, supported by Sodexo.

“I talked to the sustainable officer at the University and learned that SUNY doesn’t allow landfill food waste – that’s the policy,” Jin explained. “Each campus is expected to solve the problem. At Binghamton, the dining halls give wasted food to farmers to feed their livestock. I thought maybe we could try to directly convert that food waste into biodegradable plastics. There was little information from research publications about the feasibility of this idea, so we felt like maybe that was the gap we could work on.”

The research addressed key questions about practical application. The team found that food waste could be stored for up to a week without affecting the conversion process, making industrial-scale collection more feasible. They also studied whether certain types of food waste influenced results.

“We discovered that the process is very robust, as long as we have different types of food mixed in at the same ratio,” Jin said. “We control the temperature and the pH during fermentation, and those conditions encourage organic acid-producing bacteria to grow.”

The researchers even identified an additional use for leftover residue from fermentation. The paste-like by-product is being developed into organic fertiliser as an alternative to conventional chemical mixes.

Looking ahead, Jin plans to expand the process beyond the laboratory.

“For the next step,” she said, “I would like to scale up the process to make sure it continues to perform as expected with expanding plastic production. That means seeking more grant funding or teaming up with an industrial partner.”